I've just watched the Howard Zinn doc "...Moving Train" and am in the middle of watching the Noam Chomsky doc "Manufacturing Consent" (both again), and revived my realization that Zinn had been and Chomsky has been amazing activists. I found this 2013 piece by Chomsky at chomsky.info, and think it is

superb. He refers to Mondragon, Ohio, and Alperovitz, and his own bright light, Dewey. I wasn't familiar with Dewey's powerful relevance. I guess one thing he doesn't seem to acknowledge is the existence of Federal laws like Germany's Worker Co-Determination law with some other European Work Councils. The original Danish approach from protests to mechanics to associations to co-ops was followed by Germany to its larger scale, with an interesting version injected into the UK. Ohio has an example applying this, I understand. An example I like in the US is that of the food co-operatives and credit unions. There are plenty of both. Nevertheless, it is the industrial strength ones that need to inspire most of us, and so I am honored again to mention Michael Moore's last film, Capitalism, with his visits to Wisconsin and San Francisco industrial co-ops.

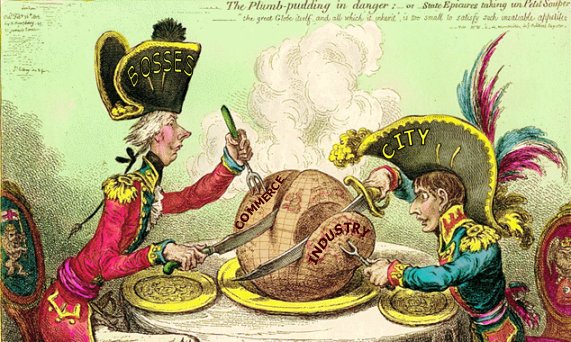

Can Civilization Survive Capitalism?

Noam Chomsky

The term "capitalism" is commonly used to refer to

the U.S. economic system, with substantial state intervention

ranging from subsidies for creative innovation to the

"too-big-to-fail" government insurance policy for banks.

The system is highly monopolized, further limiting reliance on

the market, and increasingly so: In the past 20 years the share of

profits of the 200 largest enterprises has risen sharply, reports

scholar Robert W. McChesney in his new book "Digital

Disconnect."

"Capitalism" is a term now commonly used to describe

systems in which there are no capitalists: for example, the

worker-owned Mondragon conglomerate in the Basque region of Spain,

or the worker-owned enterprises expanding in northern Ohio, often

with conservative support -- both are discussed in important work

by the scholar Gar Alperovitz.

Some might even use the term "capitalism" to refer to

the industrial democracy advocated by John Dewey, America's

leading social philosopher, in the late 19th century and early

20th century.

Dewey called for workers to be "masters of their own

industrial fate" and for all institutions to be brought under

public control, including the means of production, exchange,

publicity, transportation and communication. Short of this, Dewey

argued, politics will remain "the shadow cast on society by

big business."

The truncated democracy that Dewey condemned has been left in

tatters in recent years. Now control of government is narrowly

concentrated at the peak of the income scale, while the large

majority "down below" has been virtually

disenfranchised. The current political-economic system is a form

of plutocracy, diverging sharply from democracy, if by that

concept we mean political arrangements in which policy is

significantly influenced by the public will.

There have been serious debates over the years about whether

capitalism is compatible with democracy. If we keep to really

existing capitalist democracy -- RECD for short -- the question is

effectively answered: They are radically incompatible.

It seems to me unlikely that civilization can survive RECD and

the sharply attenuated democracy that goes along with it. But

could functioning democracy make a difference?

Let's keep to the most critical immediate problem that

civilization faces: environmental catastrophe. Policies and public

attitudes diverge sharply, as is often the case under RECD. The

nature of the gap is examined in several articles in the current

issue of Daedalus, the journal of the American Academy of Arts and

Sciences.

Researcher Kelly Sims Gallagher finds that "One hundred

and nine countries have enacted some form of policy regarding

renewable power, and 118 countries have set targets for renewable

energy. In contrast, the United States has not adopted any

consistent and stable set of policies at the national level to

foster the use of renewable energy."

It is not public opinion that drives American policy off the

international spectrum. Quite the opposite. Opinion is much closer

to the global norm than the U.S. government's policies reflect,

and much more supportive of actions needed to confront the likely

environmental disaster predicted by an overwhelming scientific

consensus -- and one that's not too far off; affecting the lives

of our grandchildren, very likely.

As Jon A. Krosnick and Bo MacInnis report in Daedalus: "Huge

majorities have favored steps by the federal government to reduce

the amount of greenhouse gas emissions generated when utilities

produce electricity. In 2006, 86 percent of respondents favored

requiring utilities, or encouraging them with tax breaks, to

reduce the amount of greenhouse gases they emit. Also in that

year, 87 percent favored tax breaks for utilities that produce

more electricity from water, wind or sunlight [ These majorities

were maintained between 2006 and 2010 and shrank somewhat after

that.

The fact that the public is influenced by science is deeply

troubling to those who dominate the economy and state policy.

One current illustration of their concern is the "Environmental

Literacy Improvement Act" proposed to state legislatures by

ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, a

corporate-funded lobby that designs legislation to serve the needs

of the corporate sector and extreme wealth.

The ALEC Act mandates "balanced teaching" of climate

science in K-12 classrooms. "Balanced teaching" is a

code phrase that refers to teaching climate-change denial, to

"balance" mainstream climate science. It is analogous to

the "balanced teaching" advocated by creationists to

enable the teaching of "creation science" in public

schools. Legislation based on ALEC models has already been

introduced in several states.

Of course, all of this is dressed up in rhetoric about teaching

critical thinking -- a fine idea, no doubt, but it's easy to think

up far better examples than an issue that threatens our survival

and has been selected because of its importance in terms of

corporate profits.

Media reports commonly present a controversy between two sides

on climate change.

One side consists of the overwhelming majority of scientists,

the world's major national academies of science, the professional

science journals and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change.

They agree that global warming is taking place, that there is a

substantial human component, that the situation is serious and

perhaps dire, and that very soon, maybe within decades, the world

might reach a tipping point where the process will escalate

sharply and will be irreversible, with severe social and economic

effects. It is rare to find such consensus on complex scientific

issues.

The other side consists of skeptics, including a few respected

scientists who caution that much is unknown -- which means that

things might not be as bad as thought, or they might be worse.

Omitted from the contrived debate is a much larger group of

skeptics: highly regarded climate scientists who see the IPCC's

regular reports as much too conservative. And these scientists

have repeatedly been proven correct, unfortunately.

The propaganda campaign has apparently had some effect on U.S.

public opinion, which is more skeptical than the global norm. But

the effect is not significant enough to satisfy the masters. That

is presumably why sectors of the corporate world are launching

their attack on the educational system, in an effort to counter

the public's dangerous tendency to pay attention to the

conclusions of scientific research.

At the Republican National Committee's Winter Meeting a few

weeks ago, Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal warned the leadership that

"We must stop being the stupid party ... We must stop

insulting the intelligence of voters."

Within the RECD system it is of extreme importance that we

become the stupid nation, not misled by science and rationality,

in the interests of the short-term gains of the masters of the

economy and political system, and damn the consequences.

These commitments are deeply rooted in the fundamentalist

market doctrines that are preached within RECD, though observed in

a highly selective manner, so as to sustain a powerful state that

serves wealth and power.

The official doctrines suffer from a number of familiar "market

inefficiencies," among them the failure to take into account

the effects on others in market transactions. The consequences of

these "externalities" can be substantial. The current

financial crisis is an illustration. It is partly traceable to the

major banks and investment firms' ignoring "systemic risk"

-- the possibility that the whole system would collapse -- when

they undertook risky transactions.

Environmental catastrophe is far more serious: The externality

that is being ignored is the fate of the species. And there is

nowhere to run, cap in hand, for a bailout.

In future, historians (if there are any) will look back on this

curious spectacle taking shape in the early 21st century. For the

first time in human history, humans are facing the significant

prospect of severe calamity as a result of their actions --

actions that are battering our prospects of decent survival.

Those historians will observe that the richest and most

powerful country in history, which enjoys incomparable advantages,

is leading the effort to intensify the likely disaster. Leading

the effort to preserve conditions in which our immediate

descendants might have a decent life are the so-called "primitive"

societies: First Nations, tribal, indigenous, aboriginal.

The countries with large and influential indigenous populations

are well in the lead in seeking to preserve the planet. The

countries that have driven indigenous populations to extinction or

extreme marginalization are racing toward destruction.

Thus Ecuador, with its large indigenous population, is seeking

aid from the rich countries to allow it to keep its substantial

oil reserves underground, where they should be.

Meanwhile the U.S. and Canada are seeking to burn fossil fuels,

including the extremely dangerous Canadian tar sands, and to do so

as quickly and fully as possible, while they hail the wonders of a

century of (largely meaningless) energy independence without a

side glance at what the world might look like after this

extravagant commitment to self-destruction.

This observation generalizes: Throughout the world, indigenous

societies are struggling to protect what they sometimes call "the

rights of nature," while the civilized and sophisticated

scoff at this silliness.

This is all exactly the opposite of what rationality would

predict -- unless it is the skewed form of reason that passes

through the filter of RECD.